“They fashioned likewise all beasts and birds in gold and silver; namely, conies, rats, lizards, serpents, butterflies, foxes, mountain cats (for they have no tame cats in their houses); and they make sparrows and all sorts of lesser birds, some flying, some perching in trees; in short, no creature that was either wild or domestic, but was made and represented by them according to its exact and natural shape.”171

Clavigero says of the exceeding skill of the Mexicans in the arts, that their works “were so admirably finished, that even the Spanish soldiers, all stung with the same wretched thirst for gold, valued the workmanship more than the materials.” And Peter Martyr, noticing the works of the people along the coasts of the Caribbean sea and the Gulf of Mexico, exclaims,—“If man’s art or invention ever got any honor in such like arts, these people may claim the chief sovereignty and commendation.”172

The method practised by the makers of the articles above mentioned, in reducing them to shape, seems to have been the very obvious one resorted to by all rude nations unacquainted with the use of iron; namely, that of rubbing or grinding upon stones possessing a sharp grit. The Mexicans, it is said, used tools of obsidian in their sculptures; and the Peruvians, although possessing implements of p273 hardened copper, according to La Vega, “rather wore out the stone by continued rubbing, than cutting.” Most of the mound-sculptures have been so carefully smoothed and are so highly polished, as to show few marks of rubbing; but some have been found, as has already been shown, in an unfinished state, which exhibit fully the mode of workmanship. These show that the makers had also sharp cutting instruments, which were used in delineating the minor features. The lines indicating the folds in the skin of animals, and the feathers of birds, are not ground in, but cut, evidently to the entire depth, at a single stroke. Sometimes the tool has slipped by, indicating that it was held and used after the manner of the gravers of the present day. The time and labor expended in perfecting these elaborate works from obstinate materials, with no other than these rude aids, must have given them a high value when finished. Hence we find a great deal of ingenuity exhibited in restoring them when accidentally broken. This was accomplished by drilling holes diagonally to each other in the detached parts, so that by the insertion of wooden pegs or copper wire, they were, in technical phrase, “bound together.” This attachment was further strengthened, in some cases, by bands of sheet copper; occasionally the entire pipe, when much injured, seems to have been plated over with that metal. When the fracture was such as materially to injure the tube, a small copper tube was inserted within it, restoring an unbroken communication. Many interesting facts of this kind, which perhaps may seem trivial and unimportant to most minds, might be presented. They illustrate how highly these remains were valued by their possessors. The manner in which the drilling was probably accomplished has already been indicated.

TABLETS.—A few small sculptured tablets have been found in the mounds. Some of these have been regarded as bearing hieroglyphical, others alphabetic inscriptions, and have been made the basis of much speculation at home and abroad. Nothing of this extraordinary character has been disclosed in the course of the investigations here recorded; nor is there any evidence that anything like an alphabetic or hieroglyphic system existed among the mound-builders. The earthworks, and the mounds and their contents, certainly indicate that, prior to the occupation of the Mississippi valley by the more recent tribes of Indians, there existed here a numerous population, agricultural in their habits, considerably advanced in the arts, and undoubtedly, in all respects, much superior to their successors. There is, however, no reason to believe that their condition was anything more than an approximation towards that attained by the semi-civilized nations of the central portions of the continent,—who themselves had not arrived at the construction of an alphabet. Whether the latter had progressed further than to a refinement upon the rude picture-writing of the savage tribes, is a question open to discussion. It would be unwarrantable therefore to assign to the race of the mounds a superiority in this respect over nations palpably so much in advance of them in all others. It would be a reversal of the teachings of history, an exception to the law of harmonious development, which it would require a large assemblage of well attested facts to sustain. Such an array of facts, it is scarcely necessary to add, we do not possess. p274

It is true, hardly a year passes unsignalized by the announcement of the discovery of tablets of stone or metal, bearing strange and mystical inscriptions,—generally reported to have a “marked resemblance to the Chinese characters.” But they either fail to withstand an analysis of the alleged circumstances attending their discovery, or resolve themselves into very simple natural productions when subjected to scientific scrutiny. It will be remembered that some years ago it was announced that six inscribed copper plates had been found in a mound near Kinderhook, Pike county, Illinois. Engravings of them and a minute description were published at the time, and widely circulated. Subsequent inquiry has shown that the plates were a harmless imposition, got up for local effect; and that the village blacksmith, with no better suggestion to his antiquarian labors than the lid of a tea-chest, was chiefly responsible for them. Within the past two years an announcement was made of the discovery, in a mound near Lower Sandusky, Ohio, of a series of oval mica plates, inscribed with numberless unknown characters, which, in the language of the printed account, probably “contained the history of some former race that inhabited this country.” These plates were found, upon examination, to be ornaments of that variety of mica known as “graphic” or “hieroglyphic mica,”—which is naturally marked with figures somewhat regular in their arrangement.

The Grave creek mound was also said to have contained a small stone, bearing an alphabetical inscription, which has attracted the attention of a number of learned men both in this country and in Europe. A critical examination of the circumstances attending the introduction of this relic to the world is calculated to throw great doubt upon its genuineness. The fact that it is not mentioned by intelligent observers writing from the spot at the time of the excavation of the mound, and that no notice of its existence was made public until after the opening of the mound for exhibition, joined to the strong presumptive evidence against the occurrence of anything of the kind, furnished by the antagonistic character of all the ancient remains of the continent, so far as they are known,—are insuperable objections to its reception. Until it is better authenticated, it should be entirely excluded from a place among the antiquities of our country.173

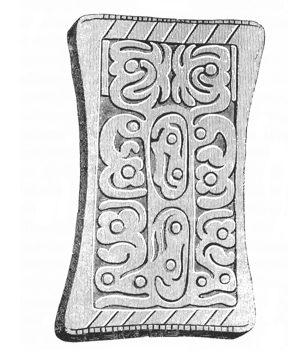

A small tablet was discovered, some years ago, in a mound at Cincinnati, of which Fig. 194 presents a front, and Fig. 195 a reverse view.

This relic is now in the possession of ERASMUS GEST, Esq., of Cincinnati. The circumstances under which it was discovered are thus detailed by Mr. Gest in a letter published at the time:

“I herewith send you what I deem to be a hieroglyphical stone, which was found buried with a skeleton in the ‘old mound,’ situated in the western part of the city, together with two pointed bones, each about seven inches long, taken from the same spot. (See page 220.)

“In the course of the excavation several skeletons were disinterred; and their being generally in a good state of preservation and near the surface, gave rise to p275 the inference that they were deposited there since the mound was erected: but the one with which the sharpened bones and hieroglyphical stone were found, was in a decayed state. Being in the centre and rather below the level of the surrounding ground, it was no doubt the object over which the mound was erected. I have a part of the skull; the remainder of the skeleton was destroyed by the diggers.”

Fig. 194. From a drawing by H. C. GROSVENOR.

The position of the skeleton with which it was found, as also the other circumstances attending the discovery of this relic, leave little doubt as to its authenticity. It was discovered in December, 1841. The material is a fine-grained, compact sandstone, of a light brown color. It measures five inches in length, three in breadth at the ends, two and six tenths at the middle, and is about half an inch in thickness. The sculptured face varies very slightly from a perfect plane. The figures are cut in low relief, (the lines being not more than one twentieth of an inch in depth,) and occupy a rectangular space four inches and two tenths long, by two and one tenth wide. The sides of the stone, it will be observed, are slightly concave. Right lines are drawn across the face near the ends. At right angles and exterior to these are notches, twenty-five at one end, and twenty-four at the other. Extending diagonally inward are fifteen longer lines, eight at one end and seven at the other. The back of the stone has three deep, longitudinal grooves, and several depressions, evidently caused by rubbing,—probably produced in sharpening the instrument used in the sculpture.

Without discussing the “singular resemblance which the relic bears to the Egyptian cartouch,” it will be sufficient to direct attention to the reduplication of p276 the figures, those upon one side corresponding with those upon the other, and the two central ones being also alike. It will be observed that there are but three scrolls or figures, four of one description, and two of each of the others. Probably no serious discussion of the question whether or not these figures are hieroglyphical is needed. They more resemble the stalk and flowers of a plant than anything else in nature. What significance, if any, may attach to the peculiar markings or graduations at the ends, it is not undertaken to say. The sum of the products of the longer and shorter lines (24×7+25×8) is 368, three more than the number of days in the year; from which circumstance the suggestion has been advanced that the tablet had an astronomical origin, and constituted some sort of a calendar.

We may perhaps find the key to its purposes in a very humble but not therefore less interesting class of Southern remains. Both in Mexico and in the mounds of Mississippi have been found stamps of burned clay, the faces of which are covered with figures, fanciful or imitative, all in low relief, like the face of a stereotype plate. These were used in impressing ornaments upon the clothes or prepared skins of the people possessing them. They exhibit the concavity of the sides to be observed in the relic in question, intended doubtless for greater convenience in holding and using it, as also a similar reduplication of the ornamental figures,—all betraying a common purpose. This explanation is offered hypothetically as being entirely consistent with the general character of the mound remains; which, taken together, do not warrant us in looking for anything that might not well pertain to a very simple, not to say rude, people.174

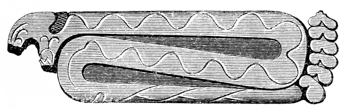

Fig. 196. From one of the mounds, numbered 1 in the plan of the great enclosure on the North Fork of Paint creek, (Plate X,) were taken several singularly sculptured tablets, of one of which the figure here presented is a copy, so far as it has been found possible to restore it from the several fragments recovered. It represents a coiled rattlesnake; both faces of the tablet being identical in p277 sculpture, excepting that one is plane, the other slightly convex. The material is a very fine cinnamon-colored sandstone, and the style of the sculpture is identical with that displayed in the tablet from the Cincinnati mound already noticed. The original is six inches and a quarter long, one and three eighths broad, and one quarter of an inch thick. The workmanship is delicate, and the characteristic feature of the rattlesnake perfectly represented. It is to be regretted that it is impossible to restore the head, which, so far as it can be made out, has some peculiar and interesting features,—plumes or ornamental figures surmounting it. Previous to the investigation of the mound by the authors, an entire tablet was obtained from it by an individual residing near the spot, who represents it to have been carefully and closely enveloped in sheets of copper, which he had great difficulty in removing. Incited by a miserable curiosity he broke the specimen, to ascertain its composition; and the larger portion, including the head, was subsequently lost. The remaining fragment, from its exceedingly well preserved condition, confirms the statement of the finder respecting its envelopment. It seems that several of these tablets were originally deposited in the mound; the greater portions of four have been recovered, but none displaying the head entire. The person above mentioned affirms that the head, in the specimen which he discovered, was surrounded by “feathers;” how far this is confirmed by the fragment, the reader must judge for himself. The tablets seem to have been originally painted of different colors: a dark red pigment is yet plainly to be seen in the depressions of some of the fragments; others had been painted of a dense black color.

It does not appear probable that these relics were designed for ornaments. On the contrary, the circumstances under which they were discovered render it likely that they had a superstitious origin, and were objects of high regard and perhaps of worship. It has already been observed, in connection with the account of the great serpentine structure in Adams county, Ohio, (Plate XXXV,) that the serpent entered widely into the superstitions of the American nations, savage and semi-civilized, and was conspicuous among their symbols as the emblem of the greatest gods of their mythology, both good and evil. And wherever it appears, whether among the carvings of the Natchez (who, according to Charlevoix, placed it upon their altars as an object of worship), among the paintings of the Aztecs, or upon the temples of Central America, it is worthy of remark, that it is invariably the rattlesnake. And as among the Egyptians the cobra was the sign of royalty, so among the Mexicans the rattlesnake was an emblem of kingly power and dominion. As such it appears in the crown of Tezcatlipoca, the Brahma of the Aztec pantheon, and in the helmets of the warrior priests of that divinity. The feather-headed rattlesnake, it should be observed, was in Mexico the peculiar symbol of Tezcatlipoca, otherwise symbolized as the sun.

-

FOOTNOTES TO CHAPTER XV.

-

159 Researches, vol. i, p. 43.

-

160 In the possession of J. VAN CLEVE, Esq., Dayton, Ohio.

-

161 See memoir on the Grave creek mound by H. R. Schoolcraft, Esq., Transactions of American Ethnological Society, vol. i. p. 408. The original is regarded by that gentleman as furnishing tangible evidence of the existence of idol worship among the North American tribes. Its purposes, whatever they were, seem to differ but slightly from those to which the ruder articles noticed in the text were applied. The orifices in the back are supposed by Mr. Schoolcraft to be designed for the insertion of the thumb and finger in lifting the object, or for the introduction of a thong or cord in transporting or suspending it.

-

162 In the collection of JAMES MCBRIDE, Esq.

-

163 Several of these masks are embraced in the collection of Mexican antiques, presented by Mr. POINSETT to the American Philosophical Society, at Philadelphia.

-

164 Godman’s American Natural History, vol. ii. p. 154.

-

165 Desm. Nouv. Hist Nat., xvii. p. 213.

-

166 Observations on the Geology of East Florida, by T. A. Conrad. Silliman’s Journal of Arts and Sciences for July, 1846.

-

167 Butram’s Travels in North America, p. 299.

-

168 Humboldt’s Travels and Researches in South America.

-

169 Godman’s Natural History, vol. ii. p. 155.

-

170 Mr. Schoolcraft mentions, in illustration of the extent of Indian exchanges in shells and ornaments, that he saw at the foot of Lake Superior, Indian articles ornamented with the shining white Dentalium Elephanticum from the mouth of the Columbia.

-

171 Commentaries of Peru. Book vi. p. 187.

-

172 De Orbo Novo, Dec. 4, cap. 9.

-

173 For a critical examination of the question of the authenticity of this relic, see Transactions of American Ethnological Society, vol. ii.

-

174 The following just observations are from the published notice of this relic, accompanying the communication of Mr. Gest, above quoted:

“The relic found here was with a skeleton, in the very centre of the mound, and all the external evidence favors the belief that it was placed there when the tumulus was raised. But the best evidence of its genuineness is this, that a person in our times could scarcely make so perfect an engraving as this stone, and not make it more perfect, the engraving represents something, whatever it is, the two sides of which are intended to be alike, and yet no two curves or lines are precisely alike, nor is there the least evidence of the use of our instruments to be discovered in the work. So difficult is it to imitate with our cultivated hands and eyes the peculiar imperfection of this cutting, that some excellent judges, who at first doubted the genuineness of the relic, have changed their opinion upon trying to imitate it. What the sculpture means is another matter.”

-