The Portrait of Rizal, Painted in Oil by Juan Luna in Paris.

Page 7Such protection was not given the subjects of Spain, but still, with all the laxity of the Spanish law, and even if all the charges had been true, which they were far from being, no case was made out against Doctor Rizal at his trial. According to the laws then in effect, he was unfairly convicted and he should be considered innocent; for this reason his life will be studied to see what kind of hero he was, and no attempt need be made to plead good character and honest intentions in extenuation of illegal acts. Rizal was ever the advocate of law, and it will be found, too, that he was always consistently law-abiding.

Though they are in the Orient, the Filipinos are not of it. Rizal once said, upon hearing of plans for a Philippine exhibit at a European World’s Fair, that the people of Europe would have a chance to see themselves as they were in the Middle Ages. With allowances for the changes due to climate and for the character of the country, this statement can hardly be called exaggerated. The Filipinos in the last half of the nineteenth century were not Orientals but mediæval Europeans—to the credit of the early Castilians but to the discredit of the later Spaniards.

The Filipinos of the remoter Christian barrios, whom Rizal had in mind particularly, were in customs, beliefs and advancement substantially what the descendants of Legaspi’s followers might have been had these been shipwrecked on the sparsely inhabited islands of the Archipelago and had their settlement remained shut off from the rest of the world.

Except where foreign influence had accidentally crept in at the ports, it could truthfully be said that scarcely perceptible advance had been made in three hundred years. Succeeding Spaniards by their misrule not only added little to the glorious achievement of their ancestors, but seemed Page 8to have prevented the natural progress which the land would have made.

In one form or another, this contention was the basis of Rizal’s campaign. By careful search, it is true, isolated instances of improvement could be found, but the showing at its very best was so pitifully poor that the system stood discredited. And it was the system to which Rizal was opposed.

The Spaniards who engaged in public argument with Rizal were continually discovering, too late to avoid tumbling into them, logical pitfalls which had been carefully prepared to trap them. Rizal argued much as he played chess, and was ever ready to sacrifice a pawn to be enabled to say “check.” Many an unwary opponent realized after he had published what he had considered a clever answer that the same reasoning which scored a point against Rizal incontrovertibly established the Kalamban’s major premise.

Superficial antagonists, to the detriment of their own reputations, have made much of what they chose to consider Rizal’s historical errors. But history is not merely chronology, and his representation of its trend, disregarding details, was a masterly tracing of current evils to their remote causes. He may have erred in some of his minor statements; this will happen to anyone who writes much, but attempts to discredit Rizal on the score of historical inaccuracy really reflect upon the captious critics, just as a draftsman would expose himself to ridicule were he to complain of some famous historical painting that it had not been drawn to exact scale. Rizal’s writings were intended to bring out in relief the evils of the Spanish system of the government of the Filipino people, just as a map of the world may put the inhabited portions of the earth in greater prominence than those portions that are not inhabited. Neither is exact in its representation, but Page 9each serves its purpose the better because it magnifies the important and minimizes the unimportant.

In his disunited and abased countrymen, Rizal’s writings aroused, as he intended they should, the spirit of nationality, of a Fatherland which was not Spain, and put their feet on the road to progress. What matters it, then, if his historical references are not always exhaustive, and if to make himself intelligible in the Philippines he had to write in a style possibly not always sanctioned by the Spanish Academy? Spain herself had denied to the Filipinos a system of education that might have made a creditable Castilian the common language of the Archipelago. A display of erudition alone does not make an historian, nor is purity, propriety and precision in choosing words all there is to literature.

Rizal charged Spain unceasingly with unprogressiveness in the Philippines, just as he labored and planned unwearyingly to bring the Filipinos abreast of modern European civilization. But in his appeals to the Spanish conscience and in his endeavors to educate his countrymen he showed himself as practical as he was in his arguments, ever ready to concede nonessentials in name and means if by doing so progress could be made.

Because of his unceasing efforts for a wiser, better governed and more prosperous Philippines, and because of his frank admission that he hoped thus in time there might come a freer Philippines, Rizal was called traitor to Spain and ingrate. Now honest, open criticism is not treason, and the sincerest gratitude to those who first brought Christian civilization to the Philippines should not shut the eyes to the wrongs which Filipinos suffered from their successors. But until the latest moment of Spanish rule, the apologists of Spain seemed to think that they ought to be able to turn away the wrath evoked by the cruelty and incompetence that ran riot during centuries, by dwelling Page 10upon the benefits of the early days of the Spanish dominion.

Wearisome was the eternal harping on gratitude which at one time was the only safe tone for pulpit, press and public speech; it irritating because it ignored questions of current policy, and it was discouraging to the Filipinos who were reminded by it of the hopeless future for their country to which time had brought no progress. But with all the faults and unworthiness of the later rulers, and the inane attempts of their parasites to distract attention from these failings, there remains undimmed the luster of Spain’s early fame. The Christianizing which accompanied her flag upon the mainland and islands of the New World is its imperishable glory, and the transformation of the Filipino people from Orientals into mediæval Europeans through the colonizing genius of the early Castilians, remains a marvel unmatched in colonial history and merits the lasting gratitude of the Filipino.

Doctor Rizal satirized the degenerate descendants and scored the unworthy successors, but his writings may be searched in vain for wholesale charges against the Spanish nation such as Spanish scribblers were forever directing against all Filipinos, past, present and future, with an alleged fault of a single one as a pretext. It will be found that he invariably recognized that the faithful first administrators and the devoted pioneer missionaries had a valid claim upon the continuing gratitude of the people of Tupa’s and Lakandola’s land.

Rizal’s insight discerned, and experience has demonstrated, that Legaspi, Urdaneta and those who were like them, laid broad and firm foundations for a modern social and political organization which could be safely and speedily established by reforms from above. The early Christianizing civilizers deserve no part of the blame for the fact that Philippine ports were not earlier opened Page 11to progress, but much credit is due them that there is succeeding here an orderly democracy such as now would be impossible in any neighboring country.

The Philippine patriot would be the first to recognize the justice of the selection of portraits which appear with that of Rizal upon the present Philippine postage stamps, where they serve as daily reminders of how free government came here.

The constancy and courage of a Portuguese sailor put these Islands into touch with the New World with which their future progress was to be identified. The tact and honesty of a civil official from Mexico made possible the almost bloodless conquest which brought the Filipinos under the then helpful rule of Spain. The bequest of a far-sighted early philanthropist was the beginning of the water system of Manila, which was a recognition of the importance of efforts toward improving the public health and remains a reminder of how, even in the darkest days of miseries and misgovernment, there have not been wanting Spaniards whose ideal of Spanish patriotism was to devote heart, brain and wealth to the welfare of the Filipinos. These were the heroes of the period of preparation.

The life of the one whose story is told in these pages was devoted and finally sacrificed to dignify their common country in the eyes of his countrymen, and to unite them in a common patriotism; he inculcated that self-respect which, by leading to self-restraint and self-control, makes self-government possible; and sought to inspire in all a love of ordered freedom, so that, whether under the flag of Spain or any other, or by themselves, neither tyrants (caciques) nor slaves (those led by caciques) would be possible among them.

And the change itself came through an American President who believed, and practiced the belief, that nations Page 12owed obligations to other nations just as men had duties toward their fellow-men. He established here Liberty through Law, and provided for progress in general education, which should be a safeguard to good government as well, for an enlightened people cannot be an oppressed people. Then he went to war against the Philippines rather than deceive them, because the Filipinos, who repeatedly had been tricked by Spain with unfulfilled promises, insisted on pledges which he had not the power to give. They knew nothing of what was meant by the rule of the people, and could not conceive of a government whose head was the servant and not the master. Nor did they realize that even the voters might not promise for the future, since republicanism requires that the government of any period shall rule only during the period that it is in the majority. In that war military glory and quick conquest were sacrificed to consideration for the misled enemy, and every effort was made to minimize the evils of warfare and to gain the confidence of the people. Retaliation for violations of the usages of civilized warfare, of which Filipinos at first were guilty through their Spanish training, could not be entirely prevented, but this retaliation contrasted strikingly with the Filipinos’ unhappy past experiences with Spanish soldiers. The few who had been educated out of Spain and therefore understood the American position were daily reënforced by those persons who became convinced from what they saw, until a majority of the Philippine people sought peace. Then the President of the United States outlined a policy, and the history and constitution of his government was an assurance that this policy would be followed; the American government then began to do what it had not been able to promise.

The forerunner and the founder of the present regime in these Islands, by a strange coincidence, were as alike Page 13in being cruelly misunderstood in their lifetimes by those whom they sought to benefit as they were in the tragedy of their deaths, and both were unjustly judged by many, probably well-meaning, countrymen.

Magellan, Legaspi, Carriedo, Rizal and McKinley, heroes of the free Philippines, belonged to different times and were of different types, but their work combined to make possible the growing democracy of to-day. The diversity of nationalities among these heroes is an added advantage, for it recalls that mingling of blood which has developed the Filipinos into a strong people.

England, the United States and the Philippines are each composed of widely diverse elements. They have each been developed by adversity. They have each honored their severest critics while yet those critics lived. Their common literature, which tells the story of human liberty in its own tongue, is the richest, most practical and most accessible of all literature, and the popular education upon which rests the freedom of all three is in the same democratic tongue, which is the most widely known of civilized languages and the only unsycophantic speech, for it stands alone in not distinguishing by its use of pronouns in the second person the social grade of the individual addressed.

The future may well realize Rizal’s dream that his country should be to Asia what England has been to Europe and the United States is in America, a hope the more likely to be fulfilled since the events of 1898 restored only associations of the earlier and happier days of the history of the Philippines. The very name now used is nearer the spelling of the original Philipinas than the Filipinas of nineteenth century Spanish usage. The first form was used until nearly a century ago, when it was corrupted along with so many things of greater importance. Page 14

Columbus at Barcelona. From a print in Rizal’s scrap-book.

The Philippines at first were called “The Islands of the West,” as they are considered to be occidental and not oriental. They were made known to Europe as a sequel to the discoveries of Columbus. Conquered and colonized from Mexico, most of their pious and charitable endowments, churches, hospitals, asylums and colleges, were endowed by philanthropic Mexicans. Almost as long as Mexico remained Spanish the commerce of the Philippines was confined to Mexico, and the Philippines were a part of the postal system of Mexico and dependent Page 15upon the government of Mexico exactly as long as Mexico remained Spanish. They even kept the new world day, one day behind Europe, for a third of a century longer. The Mexican dollars continued to be their chief coins till supplanted, recently, by the present peso, and the highbuttoned white coat, the “americana,” by that name was in general use long years ago. The name America is frequently to be found in the old baptismal registers, for a century or more ago many a Filipino child was so christened, and in the ’70’s Rizal’s carving instructor, because so many of the best-made articles he used were of American manufacture, gave the name “Americano” to a godchild. As Americans, Filipinos were joined with the Mexicans when King Ferdinand VII thanked his subjects in both countries for their loyalty during the Napoleonic wars. Filipino students abroad found, too, books about the Philippines listed in libraries and in booksellers’ catalogues as a branch of “Americana.”

Nor was their acquaintance confined to Spanish Americans. The name “English” was early known. Perhaps no other was more familiar in the beginning, for it was constantly execrated by the Spaniards, and in consequence secretly cherished by those who suffered wrongs at their hands.

Magellan had lost his life in his attempted circumnavigation of the globe and Elcano completed the disastrous voyage in a shattered ship, minus most of its crew. But Drake, an Englishman, undertook the same voyage, passed the Straits in less time than Magellan, and was the first commander in his own ship to put a belt around the earth. These facts were known in the Philippines, and from them the Filipinos drew comparisons unfavorable to the boastful Spaniards.

When the rich Philippine galleon Santa Ana was captured off the California coast by Thomas Candish, “three Page 16boys born in Manila” were taken on board the English ships. Afterwards Candish sailed into the straits south of “Luçon” and made friends with the people of the country. There the Filipinos promised “both themselves, and all the islands thereabouts, to aid him whensoever he should come again to overcome the Spaniards.”

Dampier, another English sea captain, passed through the Archipelago but little later, and one of his men, John Fitzgerald by name, remained in the Islands, marrying here. He pretended to be a physician, and practiced as a doctor in Manila. There was no doubt room for him, because when Spain expelled the Moors she reduced medicine in her country to a very low state, for the Moors had been her most skilled physicians. Many of these Moors who were Christians, though not orthodox according to the Spanish standard, settled in London, and the English thus profited by the persecution, just as she profited when the cutlery industry was in like manner transplanted from Toledo to Sheffield.

The great Armada against England in Queen Elizabeth’s time was an attempt to stop once for all the depredations of her subjects on Spain’s commerce in the Orient. As the early Spanish historian, Morga, wrote of it: “Then only the English nation disturbed the Spanish dominion in that Orient. Consequently King Philip desired not only to forbid it with arms near at hand, but also to furnish an example, by their punishment, to all the northern nations, so that they should not undertake the invasions that we see. A beginning was made in this work in the year one thousand five hundred and eighty-eight.”

This ingeniously worded statement omits to tell how ignominiously the pretentious expedition ended, but the fact of failure remained and did not help the prestige of Spain, especially among her subjects in the Far East. After all the boastings of what was going to happen, and Page 17all the claims of what had been accomplished, the enemies of Spain not only were unchecked but appeared to be bolder than ever. Some of the more thoughtful Filipinos then began to lose confidence in Spanish claims. They were only a few, but their numbers were to increase as the years went by. The Spanish Armada was one of the earliest of those influences which, reënforced by later events, culminated in the life work of José Rizal and the loss of the Philippines by Spain.

At that time the commerce of Manila was restricted to the galleon trade with Mexico, and the prosperity of the Filipino merchants—in large measure the prosperity of the entire Archipelago—depended upon the yearly ventures the hazard of which was not so much the ordinary uncertainty of the sea as the risk of capture by English freebooters. Everybody in the Philippines had heard of these daring English mariners, who were emboldened by an almost unbroken series of successes which had correspondingly discouraged the Spaniards. They carried on unceasing war despite occasional proclamation of peace between England and Spain, for the Spanish treasure ships were tempting prizes, and though at times policy made their government desire friendly relations with Spain, the English people regarded all Spaniards as their natural enemies and all Spanish property as their legitimate spoil.

The Filipinos realized earlier than the Spaniards did that torturing to death shipwrecked English sailors was bad policy. The result was always to make other English sailors fight more desperately to avoid a similar fate. Revenge made them more and more aggressive, and treaties made with Spain were disregarded because, as they said, Spain’s inhumanity had forfeited her right to be considered a civilized country.

It was less publicly discussed, but equally well known, that the English freebooters, besides committing countless Page 18depredations on commerce, were always ready to lend their assistance to any discontented Spanish subjects whom they could encourage into open rebellion.

The English word Filibuster was changed into “Filibusteros” by the Spanish, and in later years it came to be applied especially to those charged with stirring up discontent and rebellion. For three centuries, in its early application to the losses of commerce, and in its later use as denoting political agitation, possibly no other word in the Philippines, outside of the ordinary expressions of daily life, was so widely known, and certainly none had such sinister signification.

In contrast to this lawless association is a similarity of laws. The followers of Cortez, it will be remembered, were welcomed in Mexico as the long-expected “Fair Gods” because of their blond complexions derived from a Gothic ancestry. Far back in history their forbears had been neighbors of the Anglo-Saxons in the forests of Germany, so that the customs of Anglo-Saxon England and of the Gothic kingdom of Castile had much in common. The “Laws of the Indies,” the disregard of which was the ground of most Filipino complaints up to the very last days of the rule of Spain, was a compilation of such of these Anglo-Saxon-Castilian laws and customs as it was thought could be extended to the Americas, originally called the New Kingdom of Castile, which included the Philippine Archipelago. Thus the New England township and the Mexican, and consequently the early Philippine pueblo, as units of local government are nearly related.

These American associations, English influences, and Anglo-Saxon ideals also culminated in the life work of José Rizal, the heir of all the past ages in Philippine history. But other causes operating in his own day—the stories of his elders, the incidents of his childhood, the Page 19books he read, the men he met, the travels he made—as later pages will show—contributed further to make him the man he was.

It was fortunate for the Philippines that after the war of misunderstanding with the United States there existed a character that commanded the admiration of both sides. Rizal’s writings revealed to the Americans aspirations that appealed to them and conditions that called forth their sympathy, while the Filipinos felt confidence, for that reason, in the otherwise incomprehensible new government which honored their hero.

Rizal was already, and had been for years, without rival as the idol of his countrymen when there came, after deliberation and delay, his official recognition in the Philippines. Necessarily there had to be careful study of his life and scrutiny of his writings before the head of our nation could indorse as the corner stone of the new government which succeeded Spain’s misrule, the very ideas which Spain had considered a sufficient warrant for shooting their author as a traitor.

Finally the President of the United States in a public address at Fargo, North Dakota, on April 7, 1903—five years after American scholars had begun to study Philippine affairs as they had never been studied before—declared: ”In the Philippine Islands the American government has tried, and is trying, to carry out exactly what the greatest genius and most revered patriot ever known in the Philippines, José Rizal, steadfastly advocated,” a formal, emphatic and clear-cut expression of national policy upon a question then of paramount interest.

In the light of the facts of Philippine history already set forth there is no cause for wonder at this sweeping indorsement, even though the views so indorsed were those of a man who lived in conditions widely different from those about to be introduced by the new government. Page 20Rizal had not allowed bias to influence him in studying the past history of the Philippines, he had been equally honest with himself in judging the conditions of his own time, and he knew and applied with the same fairness the teaching which holds true in history as in every other branch of science that like causes under like conditions must produce like results, He had been careful in his reasoning, and it stood the test, first of President Roosevelt’s advisers, or otherwise that Fargo speech would never have been made, and then of all the President’s critics, or there would have been heard more of the statement quoted above which passed unchallenged, but not, one may be sure, uninvestigated.

The American system is in reality not foreign to the Philippines, but it is the highest development, perfected by experience, of the original plan under which the Philippines had prospered and progressed until its benefits were wrongfully withheld from them. Filipino leaders had been vainly asking Spain for the restoration of their rights and the return to the system of the Laws of the Indies. At the time when America came to the Islands there was among them no Rizal, with a knowledge of history that would enable him to recognize that they were getting what they had been wanting, who could rise superior to the unimportant detail of under what name or how the good came as long as it arrived, and whose prestige would have led his countrymen to accept his decision. Some leaders had one qualification, some another, a few combined two, but none had the three, for a country is seldom favored with more than one surpassingly great man at one time. Page 21Page 22

Rizal at Thirteen.

Rizal at Eighteen.

The Portrait on the Philippine Postage Stamp.

Rizal in London.

Chapter II

Rizal’s Chinese Ancestry

Clustered around the walls of Manila in the latter half of the seventeenth century were little villages the names of which, in some instances slightly changed, are the names of present districts. A fashionable drive then was through the settlement of Filipinos in Bagumbayan—the “new town” to which Lakandola’s subjects had migrated when Legaspi dispossessed them of their own “Maynila.” With the building of the moat this village disappeared, but the name remained, and it is often used to denote the older Luneta, as well as the drive leading to it.

Within the walls lived the Spanish rulers and the few other persons that the fear and jealousy of the Spaniard allowed to come in. Some were Filipinos who ministered to the needs of the Spaniards, but the greater number were Sangleyes, or Chinese, “the mechanics in all trades and excellent workmen,” as an old Spanish chronicle says, continuing: “It is true that the city could not be maintained or preserved without the Sangleyes.”

The Chinese conditions of these early days are worth recalling, for influences strikingly similar to those which affected the life of José Rizal in his native land were then at work. There were troubled times in the ancient “Middle Kingdom,” the earlier name of the corruption of the Malay Tchina (China) by which we know it. The conquering Manchus had placed their emperor on the throne so long occupied by the native dynasty whose adherents had boastingly called themselves “The Sons of Light.” The former liberal and progressive government, under which the people prospered, had grown corrupt and Page 24helpless, and the country had yielded to the invaders and passed under the terrible tyranny of the Tartars.

Yet there were true patriots among the Chinese who were neither discouraged by these conditions nor blind to the real cause of their misfortunes. They realized that the easy conquest of their country and the utter disregard by their people of the bad government which had preceded it, showed that something was wrong with themselves.

Too wise to exhaust their land by carrying on a hopeless war, they sought rather to get a better government by deserving it, and worked for the general enlightenment, believing that it would offer the most effective opposition to oppression, for they knew well that an intelligent people could not be kept enslaved. Furthermore, they understood that, even if they were freed from foreign rule, the change would be merely to another tyranny unless the darkness of the whole people were dispelled. The few educated men among them would inevitably tyrannize over the ignorant many sooner or later, and it would be less easy to escape from the evils of such misrule, for the opposition to it would be divided, while the strength of union would oppose any foreign despotism. These true patriots were more concerned about the welfare of their country than ambitious for themselves, and they worked to prepare their countrymen for self-government by teaching self-control and respect for the rights of others.

No public effort toward popular education can be made under a bad government. Those opposed to Manchu rule knew of a secret society that had long existed in spite of the laws against it, and they used it as their model in organizing a new society to carry out their purposes. Some of them were members of this Ke-Ming-Tong or Chinese Freemasonry as it is called, and it was difficult Page 25for outsiders to find out the differences between it and the new Heaven-Earth-Man Brotherhood. The three parts to their name led the new brotherhood later to be called the Triad Society, and they used a triangle for their seal.

The initiates of the Triad were pledged to one another in a blood compact to “depose the Tsing [Tartar] and restore the Ming [native Chinese] dynasty.” But really the society wanted only gradual reform and was against any violent changes. It was at first evolutionary, but later a section became dissatisfied and started another society. The original brotherhood, however, kept on trying to educate its members. It wanted them to realize that the dignity of manhood is above that of rank or riches, and seeking to break down the barriers of different languages and local prejudice, hoped to create an united China efficient in its home government and respected in its foreign relations.

* * * * *

It was the policy of Spain to rule by keeping the different elements among her subjects embittered against one another. Consequently the entire Chinese population of the Philippines had several times been almost wiped out by the Spaniards assisted by the Filipinos and resident Japanese. Although overcrowding was mainly the cause of the Chinese immigration, the considerations already described seem to have influenced the better class of emigrants who incorporated themselves with the Filipinos from 1642 on through the eighteenth century. Apparently these emigrants left their Chinese homes to avoid the shaven crown and long braided queue that the Manchu conquerors were imposing as a sign of submission—a practice recalled by the recent wholesale cutting off of queues which marked the fall of this same Manchu dynasty upon the establishment of the present republic. The patriot Chinese in Manila retained the ancient style, which somewhat Page 26resembled the way Koreans arrange their hair. Those who became Christians cut the hair short and wore European hats, otherwise using the clothing—blue cotton for the poor, silk for the richer—and felt-soled shoes, still considered characteristically Chinese.

The reasons for the brutal treatment of the unhappy exiles and the causes of the frequent accusation against them that they were intending rebellion may be found in the fear that had been inspired by the Chinese pirates, and the apprehension that the Chinese traders and workmen would take away from the Filipinos their means of gaining a livelihood. At times unjust suspicions drove some of the less patient to take up arms in self-defense. Then many entirely innocent persons would be massacred, while those who had not bought protection from some powerful Spaniard would have their property pillaged by mobs that protested excessive devotion to Spain and found their patriotism so profitable that they were always eager to stir up trouble.

One of the last native Chinese emperors, not wishing that any of his subjects should live outside his dominions, informed the Spanish authorities that he considered the emigrants evil persons unworthy of his interest. His Manchu successors had still more reason to be careless of the fate of the Manila Chinese. They were consequently ill treated with impunity, while the Japanese were “treated very cordially, as they are a race that demand good treatment, and it is advisable to do so for the friendly relations between the Islands and Japan,” to quote the ancient history once more.

Pagan or Christian, a Chinaman’s life in Manila then was not an enviable one, though the Christians were slightly more secure. The Chinese quarter was at first inside the city, but before long it became a considerable district of several streets along Arroceros near the present Page 27Botanical Garden. Thus the Chinese were under the guns of the Bastion San Gabriel, which also commanded two other Chinese settlements across the river in Tondo—Minondoc, or Binondo, and Baybay. They had their own headmen, their own magistrates and their own prison, and no outsiders were permitted among them. The Dominican Friars, who also had a number of missionary stations in China, maintained a church and a hospital for these Manila Chinese and established a settlement where those who became Christians might live with their families. Writers of that day suggest that sometimes conversions were prompted by the desire to get married—which until 1898 could not be done outside the Church—or to help the convert’s business or to secure the protection of an influential Spanish godfather, rather than by any changed belief.

Certainly two of these reasons did not influence the conversion of Doctor Rizal’s paternal ancestor, Lam-co (that is, “Lam, Esq.”), for this Chinese had a Chinese godfather and was not married till many years later.

He was a native of the Chinchew district, where the Jesuits first, and later the Dominicans, had had missions, and he perhaps knew something of Christianity before leaving China. One of his church records indicates his home more definitely, for it specifies Siongque, near the great city, an agricultural community, and in China cultivation of the soil is considered the most honorable employment. Curiously enough, without conversion, the people of that region even to-day consider themselves akin to the Christians. They believe in one god and have characteristics distinguishing them from the Pagan Chinese, possibly derived from some remote Mohammedan ancestors.

Lam-co’s prestige among his own people, as shown by his leadership of those who later settled with him in Page 28Biñan, as well as the fact that even after his residence in the country he was called to Manila to act as godfather, suggests that he was above the ordinary standing, and certainly not of the coolie class. This is borne out by his marrying the daughter of an educated Chinese, an alliance that was not likely to have been made unless he was a person of some education, and education is the Chinese test of social degree.

He was baptized in the Parian church of San Gabriel on a Sunday in June of 1697. Lam-co’s age was given in the record as thirty-five years, and the names of his parents were given as Siang-co and Zun-nio. The second syllables of these names are titles of a little more respect than the ordinary “Mr.” and “Mrs.,” something like the Spanish Don and Doña, but possibly the Dominican priest who kept the register was not so careful in his use of Chinese words as a Chinese would have been. Following the custom of the other converts on the same occasion, Lam-co took the name Domingo, the Spanish for Sunday, in honor of the day. The record of this baptism is still to be seen in the records of the Parian church of San Gabriel, which are preserved with the Binondo records, in Manila.

Chinchew, the capital of the district from which he came, was a literary center and a town famed in Chinese history for its loyalty; it was probably the great port Zeitung which so strongly impressed the Venetian traveler Marco Polo, the first European to see China.

The city was said by later writers to be large and beautiful and to contain half a million inhabitants, “candid, open and friendly people, especially friendly and polite to foreigners.” It was situated forty miles from the sea, in the province of Fokien, the rocky coast of which has been described as resembling Scotland, and its sturdy inhabitants seem to have borne some resemblance to the Page 29Scotch in their love of liberty. The district now is better known by its present port of Amoy.

Facsimile of the baptisimal record of Domingo Lam-co.

Altogether, in wealth, culture and comfort, Lam-co’s home city far surpassed the Manila of that day, which was, however, patterned after it. The walls of Manila, its paved streets, stone bridges, and large houses with spacious courts are admitted by Spanish writers to be due Page 30to the industry and skill of Chinese workmen. They were but slightly changed from their Chinese models, differing mainly in ornamentation, so that to a Chinese the city by the Pasig, to which he gave the name of “the city of horses,” did not seem strange, but reminded him rather of his own country.

Famine in his native district, or the plague which followed it, may have been the cause of Lam-co’s leaving home, but it was more probably political troubles which transferred to the Philippines that intelligent and industrious stock whose descendants have proved such loyal and creditable sons of their adopted country. Chinese had come to the Islands centuries before the Spaniards arrived and they are still coming, but no other period has brought such a remarkable contribution to the strong race which the mixture of many peoples has built up in the Philippines. Few are the Filipinos notable in recent history who cannot trace descent from a Chinese baptized in San Gabriel church during the century following 1642; until recently many have felt ashamed of these really creditable ancestors.

Soon after Lam-co came to Manila he made the acquaintance of two well-known Dominicans and thus made friendships that changed his career and materially affected the fortunes of his descendants. These powerful friends were the learned Friar Francisco Marquez, author of a Chinese grammar, and Friar Juan Caballero, a former missionary in China, who, because of his own work and because his brother held high office there, was influential in the business affairs of the Order. Through them Lam-co settled in Biñan, on the Dominican estate named after “St. Isidore the Laborer.” There, near where the Pasig river flows out of the Laguna de Bay, Lam-co’s descendants were to be tenants until another government, not yet born, and a system unknown in his day, should Page 31end a long series of inevitable and vexatious disputes by buying the estate and selling it again, on terms practicable for them, to those who worked the land.

The Filipinos were at law over boundaries and were claiming the property that had been early and cheaply acquired by the Order as endowment for its university and other charities. The Friars of the Parian quarter thought to take those of their parishioners in whom they had most confidence out of harm’s way, and by the same act secure more satisfactory tenants, for prejudice was then threatening another indiscriminate massacre. So they settled many industrious Chinese converts upon these farms, and flattered themselves that their tenant troubles were ended, for these foreigners could have no possible claim to the land. The Chinese were equally pleased to have safer homes and an occupation which in China placed them in a social position superior to that of a tradesman.

Domingo Lam-co was influential in building up Tubigan barrio, one of the richest parts of the great estate. In name and appearance it recalled the fertile plains that surrounded his native Chinchew, “the city of springs.” His neighbors were mainly Chinchew men, and what is of more importance to this narrative, the wife whom he married just before removing to the farm was of a good Chinchew family. She was Inez de la Rosa and but half Domingo’s age; they were married in the Parian church by the same priest who over thirty years before had baptized her husband.

Her father was Agustin Chinco, also of Chinchew, a rice merchant, who had been baptized five years earlier than Lam-co. His baptismal record suggests that he was an educated man, as already indicated, for the name of his town proved a puzzle till a present-day Dominican missionary from Amoy explained that it appeared to be the combined names for Chinchew in both the common Page 32and literary Chinese, in each case with the syllable denoting the town left off. Apparently when questioned from what town he came, Chinco was careful not to repeat the word town, but gave its name only in the literary language, and when that was not understood, he would repeat it in the local dialect. The priest, not understanding the significance of either in that form, wrote down the two together as a single word. Knowledge of the literary Chinese, or Mandarin, as it is generally called, marked the educated man, and, as we have already pointed out, education in China meant social position. To such minute deductions is it necessary to resort when records are scarce, and to be of value the explanation must be in harmony with the conditions of the period; subsequent research has verified the foregoing conclusions.

Agustin Chinco had also a Chinese godfather and his parents were Chin-co and Zun-nio. He was married to Jacinta Rafaela, a Chinese mestiza of the Parian, as soon after his baptism as the banns could be published. She apparently was the daughter of a Christian Chinese and a Chinese mestiza; there were too many of the name Jacinta in that day to identify which of the several Jacintas she was and so enable us to determine the names of her parents. The Rafaela part of her name was probably added after she was grown up, in honor of the patron of the Parian settlement, San Rafael, just as Domingo, at his marriage, added Antonio in honor of the Chinese. How difficult guides names then were may be seen from this list of the six children of Agustin Chinco and Jacinta Rafaela: Magdalena Vergara, Josepha, Cristoval de la Trinidad, Juan Batista, Francisco Hong-Sun and Inez de la Rosa.

The father-in-law and the son-in-law, Agustin and Domingo, seem to have been old friends, and apparently of the same class. Lam-co must have seen his future wife, Page 33the youngest in Chinco’s numerous family, grow up from babyhood, and probably was attracted by the idea that she would make a good housekeeper like her thrifty mother, rather than by any romantic feelings, for sentiment entered very little into matrimony in those days when the parents made the matches. Possibly, however, their married life was just as happy, for divorces then were not even thought of, and as this couple prospered they apparently worked well together in a financial way.

The next recorded event in the life of Domingo Lam-co and his wife occurred in 1741 when, after years of apparently happy existence in Biñan, came a great grief in the loss of their baby daughter, Josepha Didnio, probably named for her aunt. She had lived only five days, but payments to the priest for a funeral such as was not given to many grown persons who died that year in Biñan show how keenly the parents felt the loss of their little girl. They had at the time but one other child, a boy of ten, Francisco Mercado, whose Christian name was given partly because he had an uncle of the same name, and partly as a tribute of gratitude to the friendly Friar scholar in Manila. His new surname suggests that the family possessed the commendable trait of taking pride in its ancestry.

Among the Chinese the significance of a name counts for much and it is always safe to seek a reason for the choice of a name. The Lam-co family were not given to the practice of taking the names of their god-parents. Mercado recalls both an honest Spanish encomendero of the region, also named Francisco, and a worthy mestizo Friar, now remembered for his botanical studies, but it is not likely that these influenced Domingo Lam-co in choosing this name for his son. He gave his boy a name which in the careless Castilian of the country was but a Spanish translation of the Chinese name by which his Page 34ancestors had been called. Sangley, Mercado and Merchant mean much the same; Francisco therefore set out in life with a surname that would free him from the prejudice that followed those with Chinese names, and yet would remind him of his Chinese ancestry. This was wisdom, for seldom are men who are ashamed of their ancestry any credit to it.

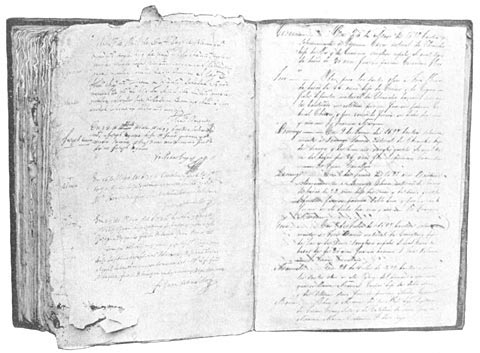

The family history has to be gleaned from partially preserved parochial registers of births, marriages and deaths, incomplete court records, the scanty papers of the estates, a few land transfers, and some stray writings that accidentally have been preserved with the latter. The next event in Domingo’s life which is revealed by them is a visit to Manila where in the old Parian church he acted as sponsor, or godfather, at the baptism of a countryman, and a new convert, Siong-co, whose granddaughter was, we shall see, to marry a grandson of Lam-co’s, the couple becoming Rizal’s grandparents.

Francisco was a grown man when his mother died and was buried with the elaborate ceremonies which her husband’s wealth permitted. There was a coffin, a niche in which to put it, chanting of the service and special prayers. All these involved extra cost, and the items noted in the margin of her funeral record make a total which in those days was a considerable sum. Domingo outlived Mrs. Lam-co by but a few years, and he also had, for the time, an expensive funeral. Page 35Page 36