CHAPTER XI.

TULJAJEE AND SERFOGEE.

Meanwhile, matters were not very settled in Tanjore, and Schwartz on his return found the people almost in rebellion and the Rajah in great straits because the Government at Madras were pressing him for tribute. All was turmoil and the political atmosphere was charged with storm, into the midst of which the old missionary came to bring a little peace and confidence. His first duty was to write to Sir John Macpherson, the Governor-General, and put in a plea for a more tender consideration for his old friend the Rajah, notwithstanding all his shortcomings.

“Now my dear sir,” he writes, “will you permit an old friend to intercede for this poor country and the dejected Rajah, requesting not to use violent or coercive measures to get the immediate payment of the arrears, which would throw the country into a deplorable and ruinous state, but rather to admonish him to rule his subjects with more justice and equity.”

We get from his letters at this period references to the political trouble which was making his efforts as a missionary very difficult, the people resenting oppression, the policy of the English represented by the Company changing continually with the fluctuation of their alliance with the native rulers, agriculture at a standstill, and the sepoys in a state of mutiny because they can get no pay. “It is truly melancholy,” he writes, “that nothing but fear will incline us to do justice to them. By these means all discipline is relaxed, the officers lose that respect which is due to their rank and station, and the Sepoys become insolent. This has been the case not only in time of war, but now in the time of peace. May God help us to consider the things which belong to our peace in all respects.” But amidst these difficulties he works hard to consolidate the little gatherings of Christians which look to him as a spiritual father and is busy with the schools, the interest of the children always lying so near his heart. Schwartz is full of faith, and his sunny presence brings confidence and hope wherever he goes; of such a man one might well say that he was a happy saint with an optimistic view under the most depressing circumstances. In so many respects he was ahead of his age, seeing possibilities which had not yet been revealed to the few Missionary Societies existing, at any rate in England, and drawing confidence and encouragement from the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, which had so well supported him in all his aims.

Still the old heart searchings kept him very humble; his letters, with scarcely an exception, indicate this increasing sense of need of watchfulness and a quiet walking with God. He reminds a friend that what we want is not so much urgent petition to God in difficulty and peril but a steadfast resting upon Him, in personal and unbroken converse. He quotes how a friend once asked Francke of the Orphan House at Halle how he kept his peace of mind. The reply was “By stirring up my mind a hundred times a day! Wherever I am, whatever I do, I say ‘Blessed Jesus, have I truly a share in Thy redemption? Are my sins forgiven? Am I guided by Thy Spirit? Thine I am. Wash me again and again. Strengthen me.’ By this constant converse with Jesus I have enjoyed serenity of mind and a settled peace in my heart.”

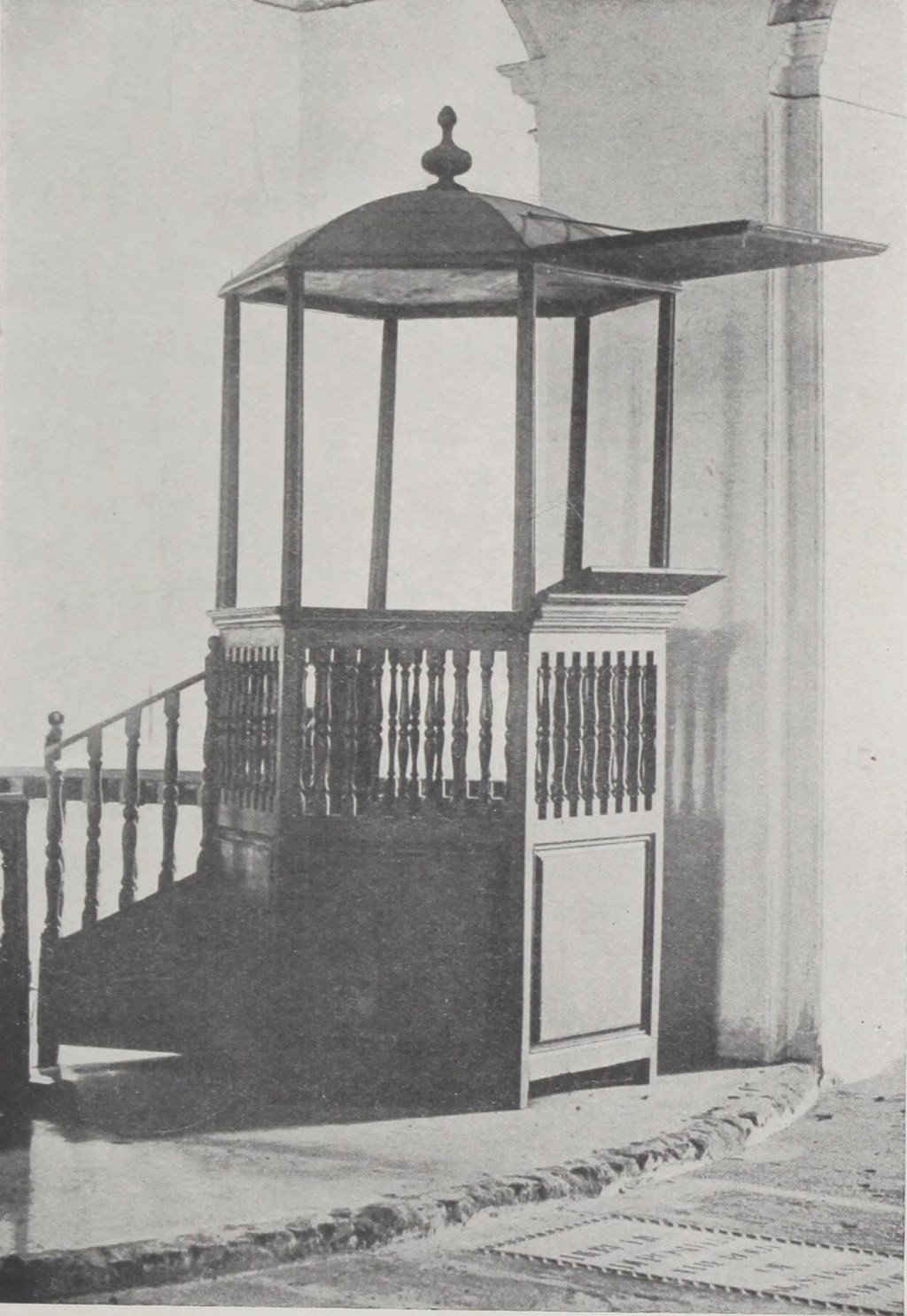

THE PILLAR BEHIND IT IS ONE ON WHICH THE RAJAH DESIGNED TO ERECT HIS MEMORIAL. IT PROVED TOO NARROW FOR THE PURPOSE

In reviewing his work from time to time he thanks God for the practical evidence of the word preached to the soldiers in his capacity as chaplain to the garrison at Tanjore. Both on Sunday and week evening services the men come in good numbers. “To this they are encouraged by their officers, who all confessed that corporal punishments had ceased from the time that the regiment began to relish religious instruction.”

He found less encouragement in dealing with Tuljajee, the Rajah of Tanjore, who, broken in health and spirit, the victim of vice and rapacity, mourning miserably the loss of his son, was rapidly going downhill. His servants were doing as they liked, and a new Sirkeel or principal officer, named Baba, was helping himself to the treasury, oppressing the poor down-trodden people. Schwartz would stand no nonsense from this man. In a letter to the English resident, Mr. Huddleston, he strongly denounces him. “If the Rajah will let him go on in this manner, my being a mediator is hypocrisy. The Rajah and Baba are entirely mistaken if they think that I would sacrifice truth or integrity to oppression and low cunning. I am heartily tired of their behaviour and shall mention it in plainest terms to them and the governor.” In the end the Government were compelled to take charge of Tanjore and in its administration asked Schwartz to take a seat on the Committee with this well deserved compliment: “Happy indeed would it be for this country, for the Company and for the Rajah himself, when his eyes should be open, if he possessed the whole authority and were invested with power to execute all the measures that his wisdom and benevolence would suggest.” He accepted this honorary position on condition that he was to be a party to no coercive measures towards the unfortunate Rajah; at the same time he will not allow his friendly interest in the past to bias him as to his attitude of injustice towards his people. “This I have declared more than once, when I humbly entreated him to have mercy on his subjects, for which plain declaration I lost in some degree his good opinion.” Soon this ruler found that his people would have nothing to do with his promises of amendment and began to leave the country in despair. The Rajah appealed to Schwartz to intervene on his behalf and such was his personal influence that seven thousand of these emigrants returned again to their homes, saying to the aged missionary, their true friend, “As you have shown kindness to us, we intend to work night and day to manifest our regard for you.”

Amongst the many friends and fellow-workers of Schwartz, the name of his young pastor, John Caspar Kohlhoff, will ever be associated. He was the son of the venerable John Balthasar Kohlhoff who for fifty years had laboured so well and faithfully in the field. It is not surprising that Schwartz took such a special interest in this young man, for he was his son in the faith. He speaks of this with great simplicity and thankfulness: “From his younger years I instructed him in Christianity, English, German and some country languages. Having been instructed for several years it pleased God to awaken him to a sense of his own sinfulness and to raise in his mind a hunger and thirst after the righteousness of Jesus. He then prayed, wept and meditated, and in short he became a very agreeable companion to me. His improvement in knowledge I observed with delight.”

And now at Tranquebar on the 23rd of January, 1787, a large congregation is gathered of Europeans and their families, with the native Christians, to the Ordination Service of this young missionary of promise. His old father sits by his side and Schwartz preaches the sermon from 2 Tim. ii. 1: “Thou therefore my son be strong in the grace that is in Christ Jesus.” After his ordination the young preacher ascended the pulpit and preached in Tamil and the meeting concluded with some faithful words from the missionaries present and the sacramental service. It was most impressive and it is a pleasure to know that the ministry thus begun was continued through many years of faithful and successful work.

The interest of Schwartz in another young man, in this instance a native prince, forms one of the most striking incidents of his work. It shows the tenderness and fatherly care, the fearless loyalty to the right and the wise direction which the old missionary devoted to one who never forgot his protector and friend. The story of Serfogee must be told here.

Tuljajee, the Rajah, according to the custom of his country, being now childless, for he had lost by death his son, his daughter, and his grandson, adopted as son the ten-year-old boy of his cousin and, after formally acquainting the English governor of the fact, on the 26th January, 1787, he sent for Schwartz to bless the child. “This is not my son,” said he, “but yours, into your hands I deliver him.” And the old missionary reverently replies: “May this child become a child of God.” Later on with much emotion the Rajah begs a favour of his friend: “I appoint you guardian of this child, I intend to give him over to your care, or literally to put his hands into yours.”

But Schwartz hesitated to take this responsibility, pointing out to the Rajah how he was leaving this boy with a support “like a garden without a fence,” and amid the bickerings and jealousies of the palace his life would be endangered and it would be difficult to protect him, though he would gladly see him from time to time. He urged him to make his brother the proper guardian of the boy. “You have a brother,” Schwartz said, “deliver the child to him, charge him to educate and treat him as his own son till he is grown up. Thus his health and life may be preserved and the welfare of the country may be secured.” To this advice the old Rajah strongly objected at first, for this brother of his was not by any means a satisfactory relative, even his legitimacy was doubtful, and it was only after an interview with his mother, who strongly supported the proposition of Schwartz, that it was agreed to.

There is no doubt that Schwartz rejected this offer of the guardianship of Serfogee because it would have placed him in a position of political responsibility in the government of the country, amounting to a regency. This, of course, would be quite incompatible with his work as a missionary. The position was a very difficult and embarrassing one, needing the utmost caution, for, on the one hand, Schwartz was anxious to stand by the boy at the affecting request of the Rajah (who had evidently not much longer to live), and, on the other hand, he must hold himself aloof from any entanglements as regards the conduct of the country during his minority. But it will be seen how lovingly and faithfully the old missionary until the day of his death fulfilled the moral guardianship of Serfogee which he from that moment accepted as a solemn charge. The next morning the decrepit and worn out Rajah summoned the English resident, Mr. Huddleston, and Colonel Stuart, the Commander of the garrison, with Mr. Schwartz to his chamber, where his brother and Serfogee with the principal officers were also assembled. He explained his will as regards the boy, agreed to his brother acting as Regent, but when Serfogee was old enough to take the throne, he trusted the Company would “maintain him and his heirs on the throne as long as the sun and moon should endure.” He was told by his visitors that this would be done and then he exclaimed: “This assurance comforts me in my last hours.”

A few days afterwards the old man died, and, although his body was burned, no woman mounted the pile to die, a significant fact, seeing that at this time the suttee was still the practice of the law. Troubles soon arose, however, over the succession; Ameer Sing was not disposed to act as simply regent and guardian, and eventually the Governor was persuaded to refer the question of title to a meeting of pundits, who, under the influence of bribes, reported that by the religious laws of the Shasters Ameer Sing should take the throne. For a time things went well, Schwartz was allowed to build schools and the money promised under the will of the late Rajah was supplied. Wherever Schwartz went the importance of providing schools for the native boys and girls was uppermost in his thoughts. At Vepery, where Lady Campbell had established an asylum for female orphans, he was much interested. “The children read to me,” he writes, “showed me their copy-books, their sewing and knitting, and recited their catechism. I expressed a wish to catechise them (by extemporaneous questions), but they were not accustomed to it. I observed ‘that mere learning by head would be of very little use to the children.’ ‘True,’ Lady Campbell answered, ‘but where shall we find persons to catechise them in a useful manner?’ I have often mentioned this subject since and trust that God will point out the means.” To these institutions the Government at Madras made liberal contributions and Schwartz asked for the same support to be granted to Tanjore. He saw how the provincial schools were succeeding at Palamcotta. These were not places where the doctrines of Christianity were taught but he always appreciated the indirect advantage to the spiritual welfare which these institutions obtained. His words are wise and explicit in speaking of the value of such schools. “They consist chiefly,” he says, in writing to the Society, “of children of Brahmins and merchants who read and write English. Their intention doubtless is to learn the English language with a view to their temporal welfare, but they thereby become better acquainted with good principles. No deceitful methods are used to bring them over to the saving doctrines of Christ; though the most earnest wishes are entertained that they may all come to the knowledge of God and of Jesus Christ whom He hath sent.”

At Tanjore one of these schools was filled with children from the best families, and the young men from the seminaries obtained good situations under the Government at Madras. Schwartz looked forward to developing in this direction a residential academy for catechists and was very anxious to start a provincial school at Combaconum, which was a very idolatrous place. But with the Rajah Ameer Sing he did not find such a favourable reception of his plans as with the old King Tuljajee, his predecessor. On this point he had the following conversation: “I spoke with the Rajah on the subject, but he seemed not to approve of it and afterwards sent to inform me of his disapprobation. I went to him and inquired how it was that he did not approve of it, especially when everyone was left at liberty to have Hindustani, Persian, Mahratta, and Malabar Schools. ‘But,’ I said, ‘the true reason of your disapprobation is a fear that many would be converted to the Christian religion. I wish you would all devote yourselves to the service of the true God. I have assisted you in many troubles and will you now treat me as an enemy? Is this right?’ He answered, ‘No, that is not my meaning, but it has never been the custom.’ ‘Ought it then,’ I replied, ‘always to remain so? There has been much done already that never was the custom.’ He said, ‘Good, good, I will do it.’”

One of the difficulties which exercised his mind especially at this time was the question of caste and here again his far sighted policy endeavoured to bring the people together, especially in divine worship. One day while waiting to see the Rajah a Brahmin challenged him, “Mr. Schwartz, do you not think it a very bad thing to touch a Pariah?” “O yes,” he replied, “a very bad thing.” The Brahmin saw that something more was meant by his answer, so he said, “But, Mr. Schwartz, what do you mean by a Pariah?” “I mean,” was the rejoinder, “a thief, a liar, a slanderer, a drunkard, an adulterer, a proud man.” “O then,” said the Brahmin hastily, “we are all Pariahs!”

Meanwhile the new Rajah of Tanjore was causing increased trouble; history was repeating itself, for he had appointed an unscrupulous man as his sirkeel who also simply exacted bribes and corrupted justice. Schwartz promptly reported this state of things to the Government at Madras and it was decided to administer the state with the help of Schwartz and Mr. Petrie, a commissioner. This led to a strong remonstrance against the confinement of the boy Serfogee in what was equal to a prison and the neglect and unkind treatment he received. There was little doubt that Ameer Sing, who had taken such solemn pledges to protect and care for him, had intended to hide him away and if possible get rid of him. It was a moment of peril for the boy and demanded instant action. Schwartz, with an English gentleman, went to the palace, asked for Serfogee and taking him by the hand told him to follow. The Rajah, alarmed, implored that the boy should not be removed, promising that he should be well cared for. Schwartz consented, but slept by the boy all night and never left him until twelve sepoys of the 23rd Regiment were set to guard. Schwartz afterwards wrote a long report to the Council at Madras, narrating the corrupt condition of the Rajah’s government and that it was imperative that the boy should be placed in more security, be properly educated and provided for. Not only so, but Schwartz prepared and submitted a clear and most able plan for the administration of justice in Tanjore. This long and statesmanlike document is a proof of his remarkable knowledge and experience of the needs of the people. “It is acknowledged,” he writes, “that the administration of justice is the basis of the true welfare of a country.”

But this excellent reform, while appreciated by the Government at Madras, did not find equal favour at the court of Tanjore. The Rajah, dissipated, diseased and weak minded, was more and more in the hands of the rapacious intriguing people around him, nominally his servants but really his masters.

In the meantime Schwartz pursued his work in spite of many hindrances, opening fresh schools and utilizing the native catechists. One of these was ordained at this time, Sattianaden, a man of high character and some talents. Schwartz, writing of his qualifications for the work of a minister, gives him high praise, “His whole deportment evinces clearly the integrity of his heart. His humble, disinterested and believing walk has been made so evident to me and others that I may say with truth I have never met with his equal among the natives in this country. His love to Christ and his desire to be useful to his countrymen are quite apparent. His gifts in preaching afford universal satisfaction. His love to the poor is extraordinary.”

The ordination of Sattianaden was a step of much importance, for it inaugurated a new era of utilizing native help in the Indian mission field. His sermon was considered by the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge to be worthy of publication and he was also much cheered by a very kind letter the secretary sent him with the good wishes of the Society for the success of his ministry. In a letter to Mr. Jaenické, his fellow worker at Palamcotta, Sattianaden makes a grateful and affectionate reference to Schwartz.

“When I contemplate the ways of God by which He led me I am full of admiration and praise. I was once a heathen, who did not know Him and He called me by His faithful servant Mr. Schwartz. This, my venerable father, received and instructed me. His exertions by day and night tended to bring me to repentance towards God and faith towards our Lord Jesus Christ, to produce in me fruits meet for repentance, to induce me to lead a Godly and holy life and to grow in knowledge and in every grace and virtue. He did not destine me to worldly concerns but appointed me to bring my nation to the knowledge of God and of Jesus Christ whom He sent to redeem the world.”

Meanwhile the work at Tanjore progressed. Schwartz mentions with thankfulness that in the year when he attained the age of sixty-five no less than eighty-seven heathen had been baptized and that he had heartily welcomed the new missionary Mr. Caemmerer at Tranquebar, who had begun well. This new comer, writing home, speaks of the anticipation he felt of meeting Schwartz and how his heart was kindled when that hope was realized. His letters contain a few pictures of the old veteran. “Sincere esteem and reverence penetrated my soul when I saw this worthy man with his snow white hair. Integrity and truth beamed in his eyes. He embraced me and thanked God that He had lead me to this country.... Nothing could possibly afford me more lively satisfaction than the society of Mr. Schwartz. His unfeigned piety, his real and conscientious attention to every branch of his duties, his sincerity—in short, his whole demeanour fills me with reverence and admiration. He treated me like a brother or rather like a tender parent and instructed me in the most agreeable manner in the Malabar language.... Many an evening passed away as if it had been but a single moment, so exceedingly interesting proved the conversation of this truly venerable man and his relations of the singular and merciful guidance of God, of which he had experienced so many proofs throughout his life, but particularly during the dreadful wars of India. The account he gave of the many dangers to which his life had been exposed and the wonderful manner in which it was often preserved, his tender and grateful affection towards God, his fervent prayers and thanksgivings, his gentle exhortations constantly to live as in the presence of God, zealously to preach the Gospel and entirely to resign ourselves to God’s kind providence—all this brought many a tear into my eyes and I could not but ardently wish that I might one day resemble Schwartz. His disinterestedness, his honourable manner of conducting public business, procured him the general esteem both of Europeans and Hindus. Every one loved and respected him, from the King of Tanjore to the humblest native.

“Nor was he less feared, for he reproved them without respect to situation and rank when their conduct deserved condemnation, and he told all persons, without distinction, what they ought to do and what to avoid, to promote their temporal and eternal welfare. The King frequently observed that in this world much was affected by presents and gold, and he himself had done much by these means, but that with Padre Schwartz they answered no purpose.... His garden is filled from morning till late in the evening with natives of every rank who come to him to have their differences settled, but rather than his missionary duties should be neglected the most important cases were delayed.

“Both morning and evening he has a service at which many of the Christians attend. A short hymn is first sung, after which he gives an exhortation on some passage of Scripture and concludes with a prayer. Till this is over, everyone, even the most respectable, is obliged to wait. The number of those who come to him to be instructed in Christianity is great. Every day individuals attend, requesting his Society to establish a Christian congregation in their part of the country.

“During my stay, about thirty persons, who had previously been instructed, were baptized. He always performs the service with such solemnity that all present are moved to tears. He has certainly received from God a most peculiar gift of teaching the truths of religion. Heathens of the highest rank, who never intend to become worshippers of the true God and disciples of Jesus Christ, hear his instructions with pleasure. During an abode of more than forty years in this country, he has acquired a profound knowledge of the customs, manners and character of the people. He expresses himself in the Tamil language as correctly as a native. He can immediately reply to any question and refutes objections so well that the people acknowledge ‘We can lay nothing to the charge of this priest.’”

One of the problems which often exercised the mind of Schwartz was how to find employment for his converts, a difficulty which is no stranger to the mission field to-day. In more senses than one the native Christian has to begin life all over again. In some cases he has made material sacrifices which he can never recover, but to all there is the right to live and the need for supplying its common necessaries. In his journal under date 1791 Schwartz makes a brief mention of the action taken in this respect:

“I sometimes employ poor widows in spinning. They bring the yarn to a Christian weaver, who makes good cloth for a trifling sum. Some widows bruise rice and sell it, others support themselves by selling fruit. When I visit these poor women on an afternoon I first catechise them and then get them to show me their work, as a proof of their industry. Labour is constantly necessary for them, not only as an occupation but to fix their minds on an object during their hours of solitude.

“The great wish of our heart is, that those who have been instructed in our religion may lead a life conformable to its holy precepts. Some indeed bring forth the fruits of faith, as for others we labour with patience, in hope of seeing them turn to the Lord.”